Has the COVID-19 pandemic leveraged an improved air quality (PM2.5) in Colombo?

BY Eng. (Professor) Mahesh Jayaweera

What is PM2.5 and how does it affect us?

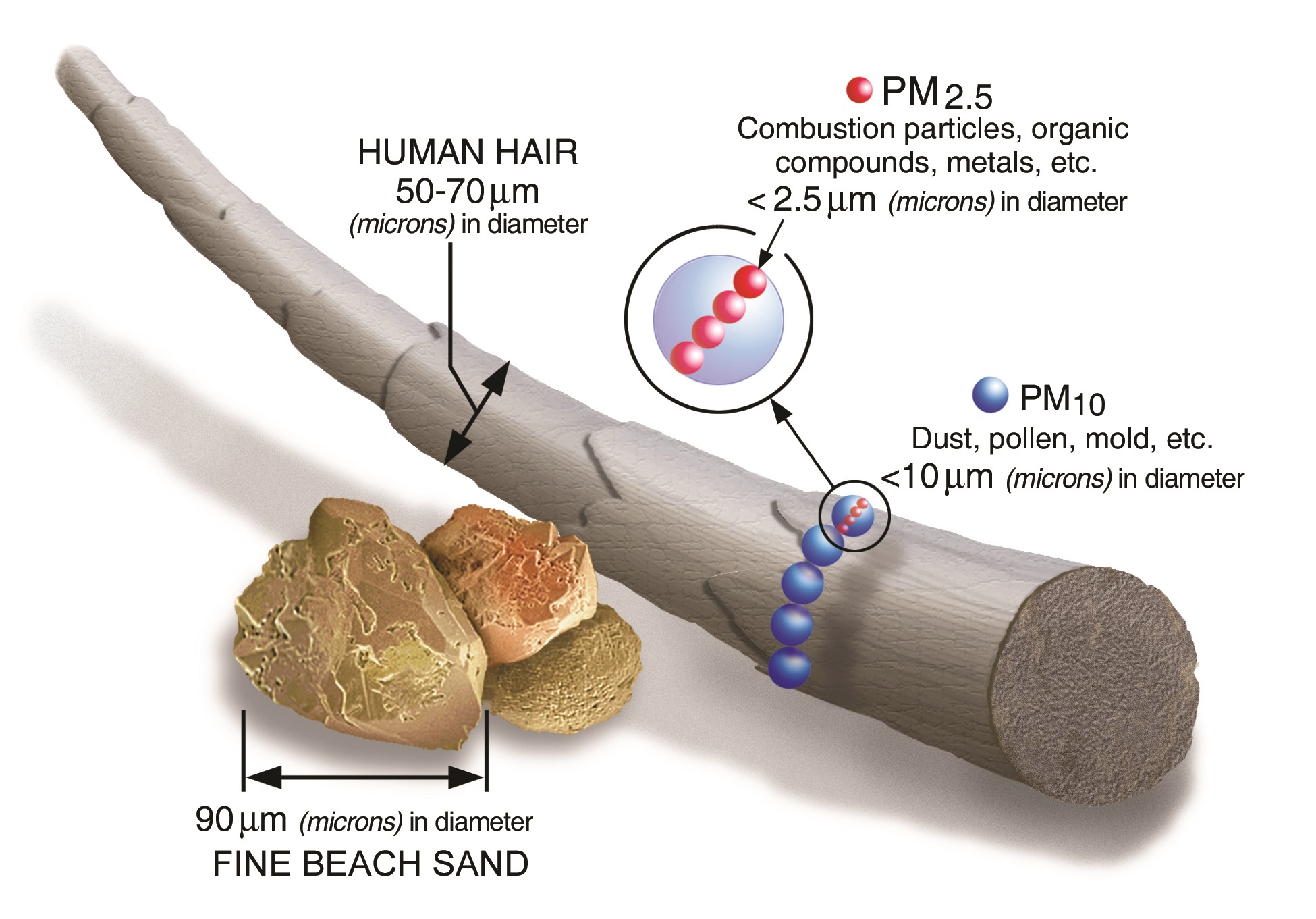

Fine particulate matter, defined as PM2.5, is an air pollutant of concern for people's health. PM2.5 are tiny particles in the air that reduce visibility and cause the air to appear hazy when levels are elevated. Have we ever contemplated the quality of the air we breathe in Colombo? Generally, an average person inhales around 20,000 breaths per day, and fine particles represented by PM2.5 are embodied in such air. The air we inhale enters through the respiratory tract to the lungs and eventually our bloodstream. These fine particulates are 25 to 100 times thinner than human hair and can cause severe risks to our health (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Size comparison of PM2.5 particles with human hair (Source: EPA)

Particles in the PM2.5 ensemble travel far deeper in the lungs and remain there for a longer period. Such a phenomenon can cause acute health effects such as eye, nose, throat and lung irritation, coughing, sneezing, runny nose and shortness of breath, among others. Exposure to high PM2.5 levels can also affect lung function, eventually leading to asthma and/or heart disease. Scientific studies have corroborated that increases in daily PM2.5 exposure with increased respiratory and cardiovascular hospital admissions, increased rates of chronic bronchitis, reduced lung function, and increased mortality from lung cancer and heart disease. People with breathing and heart problems, children and the elderly may be particularly sensitive to PM2.5.

How do we encounter elevated levels of PM2.5 in Colombo?

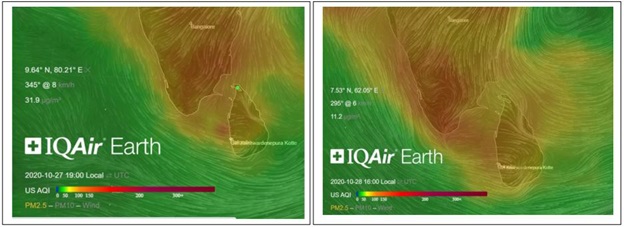

These particles assemble in many sizes and shapes and can be formed in numerous ways. Some are emitted directly from a source, such as construction sites, unpaved roads, open fields, smokestacks, etc. Major sources are attributed to power plants, industries, and automobiles. Depending on the wind pattern, Colombo manifests typical elevated levels contributed not only by nearby sources but also the sources far from Colombo, extending beyond our territorial waters. It is evident that the regional wind pattern coupled with elevated levels from other countries could hamper PM2.5 levels in Colombo. One such example as predicted by IQAir Earth software in October 2020 is illustrated in Figure 2, where Colombo seemed to have received elevated levels of PM2.5 from India.

Figure 2: Levels of PM2.5 and its direction of movement in the Indian Ocean on 27th and 28th October 2020 predicted by IQAir Earth software

Such scenarios elucidate that South-Indian emissions have been high and that there exists a great chance of Colombo being polluted with PM2.5.

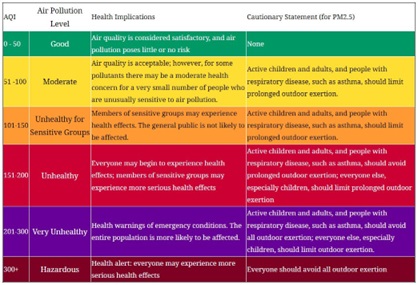

What yardstick is suitable to compare temporal variation against health effects?

One of the prominent air quality indices (AQI) developed by the US Environmental Protection Agency has been widely used in many countries to compare the suitability of air enriched with PM2.5. AQI is defined as spanning from 0 to 500, and the higher the AQI value, the greater the level of air pollution and the greater the health concern. For example, an AQI value of 50 or below represents good air quality, while an AQI value over 300 represents hazardous air quality. For each pollutant, an AQI value of 100 generally corresponds to an ambient air concentration that equals the level of the short-term national ambient air quality standard for the protection of public health. AQI values at or below 100 are generally thought of as satisfactory. When AQI values are above 100, air quality is unhealthy: first for certain sensitive groups of people, then for everyone as AQI values get higher. The AQI is divided into six categories (Figure 3). Each category corresponds to a different level of health concern. Each category also has a specific color. The color makes it easy for people to quickly determine whether air quality reaches unhealthy levels in their communities.

Figure 3: Six categories of AQI manifesting different health effects (Source: US EPA)

Has COVID-19 been a blessing in disguise in lowering PM2.5 in Colombo?

COVID-19 virus has embarked in Sri Lanka in early March 2020, and ever since, it has been found in Colombo with a varying number of casualties. The government authorities have promptly taken decisions to impose non-pharmaceutical interventions from the middle of March 2020, and lockdown status had been maintained in Colombo until early 2021. Thereafter, imposition and lifting of different restriction activities resulting in mass movement controls have been in force. Such interventions have completely haltered vehicular movement, thereby a remarkable reduction of PM2.5 levels in Colombo. The same scenario has been applied in India, but the reduction in PM2.5 levels seemed debatable.

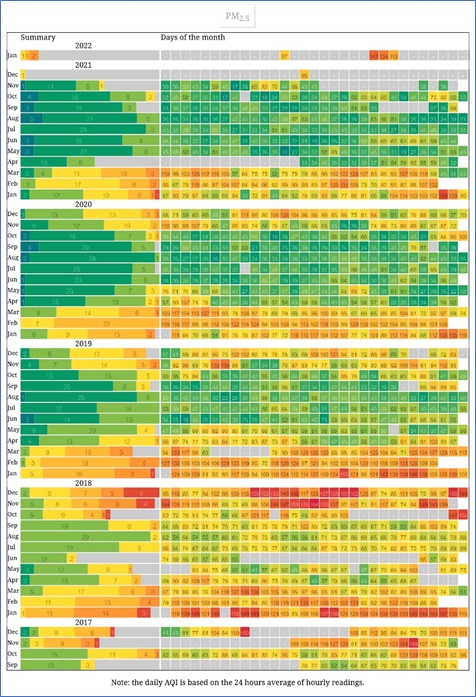

Figure 4 shows the daily variation of Colombo AQI developed by the US Embassy in Colombo in terms of PM2.5 from September 2017 to January 2022.

Figure 4: Daily variation of Colombo AQI developed by the US Embassy in terms of PM2.5 from September 2017 to January 2022 (Source: US Embassy in Sri Lanka)

When observing the collated AQIs in Colombo, it is evident that from November to March, where northeast monsoonal winds prevail, Colombo AQI becomes mostly moderate and unhealthy for sensitive groups. Conversely, from April to October, conditions become improved because southwest monsoonal winds take the pollutants away from Colombo. Nevertheless, before the COVID-19 engulfed Colombo, the improvements were insignificant or marginal under normal circumstances. However, with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the period from November to March has not shown considerable improvement, indicating that although vehicular transport has had no impact, the other sources (thermal power plants) have contributed in high magnitude. In contrast, the period from April to October has shown a considerable reduction of PM2.5 levels (about 30–40%), indicating an improved situation due to the lack of heavy vehicular fleets. When we look back at the situational improvement in 2020 and 2022, one could be complacent with achievements (green days in terms of better AQIs in Figure 4). However, such improved air quality is very unlikely to be maintained on a long-term basis at the expense of economic activities; hence, long-term interventions are of paramount importance.

Are we to expect a paradigm shift to achieve a better tomorrow with better air quality in Colombo?

The present government strives hard to bring in new strategies and policies that would yield better air quality in terms of PM2.5. Making facemasks mandatory in public places, particularly outdoors, as an effective measure for the COVID-19 pandemic would indirectly help avert inhalation of PM2.5 particles; thereby, health risks could be made minimal. Making policies to import electric vehicles in the future instead of those run with fossil fuel seems to be a gesture worth mentioning. It would invariably lessen the particulate matter released to the environment. Transforming many of the power plants run by fossil fuels in and around Colombo to ones operated by natural gas would be another pragmatic decision that the government has initiated. A major contributor to poor air quality in Colombo has been reported due to most of these power plants, and improved air quality would be plausible with planned fuel shift from oil to gas. Furthermore, the policy to go green with 70% renewables in the country is another milestone to be achieved for better air quality. Online working environment bringing the office home adopted by many companies and entities is yet another important gesture to avoid vehicular fleet in Colombo and suburbs.

However, one cannot be content even with all interventions in place, as transboundary movement, particularly from India, would impact Colombo astounding levels. Therefore, bilateral or multilateral treaties within the South Asian region are imperative to be ratified to minimize such transboundary effects. Air quality surveillance with accurate dispersion modeling coving the South Asian region seems to be an important tool in predicting such air pollutant movements, and Meteorological Department would be instrumental in playing the leading role in such efforts.

Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic has epitomized a good lesson that we could not achieve for years. Before all of us today, the critical question is whether we will go from good to bad once the Colombo is fully open for its economic activities. It is our duty to do our part to make Colombo a better place for our children, grandchildren, and generations to come. Let us all join hands to accomplish our responsibility to make a better tomorrow in Colombo with improved air for all of us to breathe. If we commit seriously, the day we breath good air in Colombo will not be far away.

Eng. (Professor) Mahesh Jayaweera

Eng. (Professor) Mahesh Jayaweera

B.Sc. (Civil Eng), Ph.D. (Env Eng)

Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Moratuwa

Chartered Engineer, Member of IESL, and SLAAS