Microplastics invading Sri Lankan Rivers

By Eng. (Prof.) Ayantha Gomes

Recent studies of Deduru Oya, conducted by the SLIIT’s Fundamental and Applied Hydraulics and Hydrology research group started in 2021, have revealed a concerning concentration of microplastics in every sample taken covering the entire river length. Although this concentration is much lower than that of many well-known rivers elsewhere, it is a clear indication that microplastics also plague Sri Lankan rivers.

Microplastics are plastics less than 5 mm in size and can be produced intentionally (primary) and unintentionally (secondary). Personal care products such as cleansers and cosmetics frequently include primary microplastics (e.g., fiber, pellets). Secondary microplastics are created when large plastics in the environment are broken into small particles. Most of the disposed plastics finally degrade and produce fragments.

Microplastics over time have become a global issue as they could accumulate inside humans and animals via the food chain causing long-term health impacts and destructive changes in growth characteristics, reproduction, behavioural characteristics and even mortality. Studies have found that even the placenta of unborn babies contains microplastics. As microplastic contains toxic chemicals they can cause serious health impacts on human bodies.

The impacts of microplastic pollution are common and not confined to a certain region as it is independent of whether the country is developed or not, industrial, or agricultural. It has now been found that microplastics even contribute to climate change. Plankton in seas sequesters 30-50 percent of the world's carbon dioxide emissions. However, plankton’s ability to perform this greatly reduces if they ingest microplastic, ultimately resulting in global warming! Although the impacts of microplastics polluting the water bodies are far-fetched, some countries like Sri Lanka remain oblivious to the growing issue.

In Sri Lanka, most of the microplastic studies are done for coastal waters. It is understandable that government agencies with limited funds would concentrate on the sea, as it is the last resting place for many contaminants including microplastics.

Having identified this knowledge gap, several inland water studies were conducted covering different types of water bodies with wide spatiotemporal coverage. One of them was the study carried out covering the entire course (i.e., from its headwaters- eastern border of the central province to the sea outfall at Chillaw) of Deduru Oya, one of the main rivers in Sri Lanka with a 142 km length, (the 6th longest). Studying microplastics in rivers would surrogate the pollution across the catchment as any microplastic intentionally dumped in water bodies or discarded in terrestrial areas would eventually be transported into water bodies such as rivers which occupy the lowest elevated points in the catchment (landscape). Therefore, studying microplastic pollution in rivers is theoretically important as it is a good indicator of the extent of the pollution and is practically important considering the high mobility and direct and indirect goods and services that humans get from rivers.

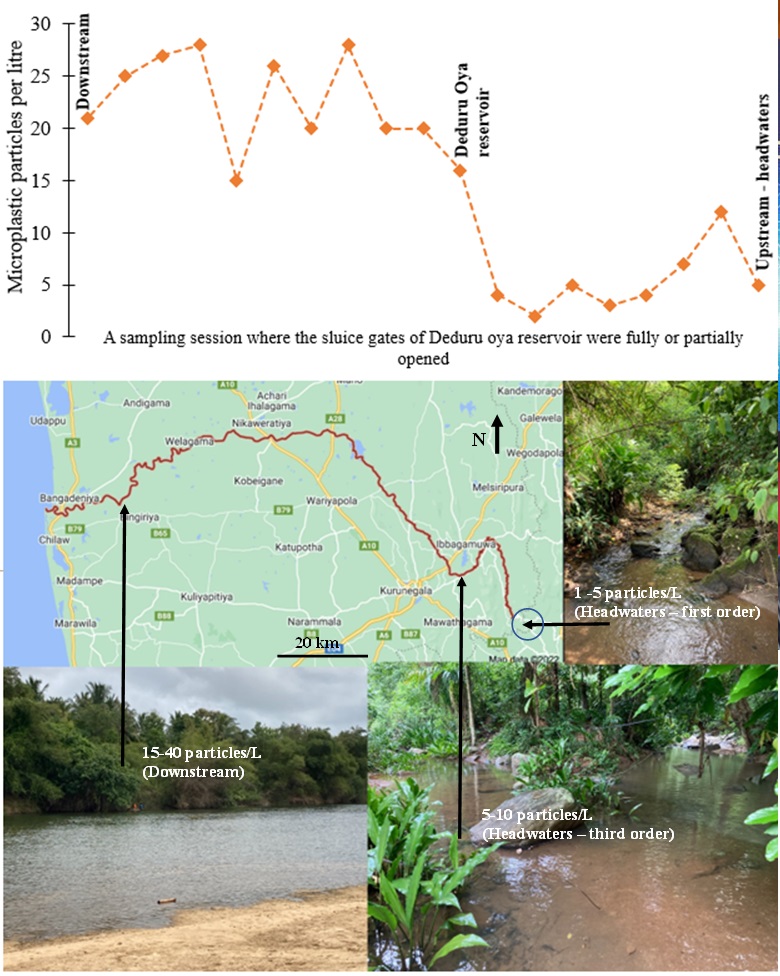

Samples were collected via a comprehensive statistically acceptable spatiotemporal sampling regime starting from first-order streams (i.e., the smallest of streams that feed larger streams but do not have any stream feeding them) to downstream most sections of Deduru Oya. The first orders were about 1 to 2 m wide whereas the downstream most were over 200 m wide. Microplastics were observed as particle and mass concentrations, and the field and laboratory blank corrections were done too. The following are six key observations were made as outcomes of the study .

- Immediate action is needed, but no need to panic: Not a single sample of Deduru oya was free from microplastics, and the fact that other rivers in Sri Lanka have the same fate, perhaps is general. Concentrations ranged from 1 to 40 in terms of particles per litre, and many rivers elsewhere in the world are reported to have exceeded even our highest concentration by two-three times.

- Headwater streams, perception of pristine streams and microplastics: The general belief is headwater streams in Sri Lanka are pristine or at least near pristine. Many headwaters of Deduru oya have catchments with over 95% of forest/vegetation, however, these too showed contamination. The reason should be the day-to-day village lifestyle activities such as using the stream for washing clothes, bathing, and other washing needs, and recreational use by visitors. This is an indication on need of awareness programs followed by actions are a must in these village setups.

- Testing common scientific hypotheses: In line with conventional understanding the microplastic contamination showed an accumulation from the source to the river mouth. However, the built area fraction showed only a weak contributing impact on microplastic concentration. Interestingly the contamination was strongly correlated with agricultural land use. Some fertilizers contain microplastics which are used as a coating for the particles to help to degrade the fertilizers slowly. Farmers use polythene tapes and bags as a method of chasing out birds and wild animals that damage crops. But this polythene will eventually fade and end up in the streams nearby. In the absence of proper centralized or decentralized treatment facilities, wastewater can get to Deduru oya via expedient connections.

- River regulation (damming): All dams (small dams such as Ridibendiella as well as the largest of all, the Deduru oya reservoir) showed localized peaks at a certain point of time such as when spillways are closed, an indication of trapping of microplastics.

It is true that the team of this study also observed much higher microplastic content in surface waters (canals and lakes) in and around Colombo. However, since these waters are not directly used, contamination may not directly impact humans. But Deduru Oya or other rivers in Sri Lanka are regularly used. This is a source of raw water in drinking water supply schemes, aquaculture and fishing are prominent too. Fortunately, the drinking water treatment methods adopted by the National Water Supply and Drainage Board remove microplastics, even though these were not developed with the intention of removing microplastic pollutants. Research is underway in this regard but what is certain is that the treatment cost will rise if water is contaminated with microplastics. Also, there are thousands of users that directly use river water with simple treatment methods. In addition, those who consume fish would also ingest microplastics.

Therefore, the findings of this study highlight the urgent need for a national level campaign to address the growing pollution of microplastics in the Sri Lankan rivers.

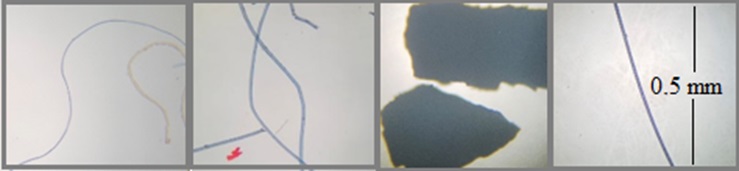

Microscopic view of some microplastics of Deduru Oya

Eng. (Prof.) Ayantha Gomes

Eng. (Prof.) Ayantha Gomes

Academic and researcher in Civil and Environmental engineering.

Chartered Engineer and reciepient of Presedential awards for scientific publications in 2014.

Specialist in water and environment with expertise on urban ecosystems, urban waterways and hydrology, headwater streams, environmental impact assessments and waste management. Real estate economics is the minor specialization with special emphasis on condominium apartments.

Has professional and academic experiences in Sri Lanka, Hong Kong (SAR), and Japan