|

To train buffs and passengers of an earlier vintage, the term ‘Garratt Locomotive’ conjures up images of mountainous track, winding curves, thunderous exhaust and mighty steam engines pounding away with lengthy trains in a now almost forgotten by-gone era. Indeed the Garratts of Sri Lanka’s railways held sway over the Upcountry Main Line for decades during the steam hauled age.

It is pertinent to consider first the beginnings of the Garratt Locomotive prior to entering in to a discussion on this fascinating machine. When steam locomotives were making headway all over the world in the late nineteenth century, many locomotive engineers in Europe were exploring designs that would enable locomotives to negotiate tight curves easily and haul heavier loads than possible with the then available rigid framed locomotives. A multitude of articulated designs resulted, foremost amongst them being the Kitson, Meyer, Double Fairlie, Shay and the renowned Mallett types. Of these, only the Mallett flourished, especially in the US, culminating in the 550 ton “Big Boy”, the largest and most powerful steam locomotive ever built. The Shay, to some extent, was also successful, but was confined mainly to narrow gauge logging operations.

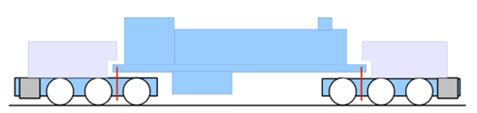

Then in the early 1900s, enter Herbert William Garratt, an Inspector for the New South Wales Government Railways in Australia. While working on designs for articulated gun or artillery carriages, Garratt hit upon the concept of an articulated locomotive with three separate frames pivoted together, enabling the end frames to swivel relative to the centre frame. This was a brilliant concept allowing the two end frames to carry water and coal tenders, with a massive boiler and deep firebox mounted on the central frame. Two separate sets of cylinders and driving gear could be installed on the end frames, making for a powerful locomotive with four cylinders, yet able to negotiate tight curves due to its articulation (Refer to Sketch 1). Although Australia has enjoyed a long tradition of local locomotive building, Garratt’s efforts to persuade the builders at the time to adopt his design fell on deaf ears. It is said that he then took his concept to the UK, where only the Manchester firm of Beyer-Peacock became sufficiently interested to try it out. The rest, as they say, is history. The Garratt locomotive, named of course after H W Garratt, went on to become one of the most successful of all articulated locomotive designs, with hundreds of units of varying size and power, being produced for the thriving British colonial railroads all over the world. Unfortunately for Herbert William Garratt, it did not bring riches as it is understood that he had sold his designs to Beyer-Peacock without recourse for continuing royalties, dying a relatively poor man at an early age.

Sri Lanka, or then Ceylon, had its first experiences with a Garratt in 1927, when the old colonial railway administration of the time got down a single locomotive, the Class C1, number 241. With a wheel arrangement of 2-6-2 + 2-6-2 it boasted a starting tractive effort of around 42,000 lbs and weighed in at a massive 123 tons. However, due to the multiplicity of its axles, the axle load was only 13.5 tons, well within the permitted loadings. Along with the 4-8-0 “Big Bank Engines”, It spent all its life hauling trains, unassisted, or assisted by a banking locomotive if the load demanded it, on the celebrated Rambukkana to Kadugannawa incline, a stretch of thirteen miles of continuous 1 in 44 gradient. Built by Beyer-Peacock, it had modern (at the time) piston valves, steam brake, superheated six foot diameter boiler mounted with triple safety valves and Belpaire square topped firebox. The coal capacity was 7 tons and its water tender held 4,000 gallons of water. It was capable of hauling unassisted, a trailing weight of around 300 tons on the incline, normally requiring two Class B1 or B2 4-6-0 tender locomotives. It was said that the resultant coal and water saving was around 20.5% and 15.5% respectively, and of course, less the crew of an additional locomotive.

For some reason, possibly due to bridge and track weight restrictions, no further Garratts were imported for nearly twenty years, the railway continuing to resort with the practice of banking or piloting with twin 4-6-0 locomotives, even on the heavily graded Upcountry Main Line. Then in 1946, Beyer-Peacock supplied eight more 2-6-2 + 2-6-2 Garratts, termed the Class C1A, the track and bridges having been strengthened by then. Although similar in design and capability to the C1, they had marginally increased weight (128 tons, the heaviest ever on Sri Lankan rail) and improved tractive effort (43,000 lbs), but had a number of modifications. Foremost amongst these were the inclusion of Nicholson thermic syphons and Hadfield steam power reversers. The thermic syphon was a funnel shaped contraption connecting the firebox roof and the front plate, permitting better circulation of water and improved thermal efficiency. The steam power reverser assisted the drivers greatly in cut-off governing of the cylinders and setting the locomotive in to reverse.

The new Garratts were all despatched to the Upcountry Main Line and were based at the Nawalapitiya shed. Like the earlier C1, they performed yeoman duty on the ruling 1 in 44 Upcountry gradient hauling trains singly or double hauling with a rigid locomotive, when trailing weights exceeded their single hauled performance capability. They were only stabled overnight at Nanu Oya, Bandarwela or Badulla, in readiness for their return trip to Nawalapitya. It was a spectacular sight to see these monsters attacking the incline on a wide open regulator, copious black smoke blasted heavenwards, with an occasional deep-throated roar from their “Bull-roarer” whistle and their thunderous asynchronous four cylinder exhaust beat reverberating across the mountainsides for miles on end! When double hauled, the Garratt was always leading at the front of the train with the less powerful 4-6-0 at the rear as the banker. Had the Garratt been the banking engine, its enormous tractive effort (60% more than that of the 4-6-0) could have led to possible train break-up and derailment, through over-run of the couplers. The Garratts always worked tender first out of Nawalapitiya to Badulla and returned bunker first back to Nawalapitiya. The only place they could be turned around (if need be) was at the Triangle at Peradeniya Junction. No turntable in Sri Lanka was able to accommodate their 74 foot length bulk. With a 45 square foot grate and its voracious appetite for coal it was no easy task to fire these locomotives. Thus in the early 1950s, all were converted to oil burning. This modification no doubt, alleviated the fireman’s chores, but led to thick acrid clouds of black smoke being emitted all the time, due to the oil burners having to be kept on continuously. Many were the stories of engine crew coming to grief overcome with smoke, especially in tunnels.

Sri Lanka was in possession of a narrow gauge Garratt as well, a diminutive 39 ton 2-4-0 + 0-4-2 locomotive imported for the 2’ 6” gauge Uda Pussellawa Railway in 1930. When that railway closed in the 1940s it was moved down to work on the Kelani Valley line.

With the rapid and somewhat hasty dieselisation that took place on Sri Lanka’s railways after 1969, these magnificent locomotives lost their pride of place and were often relegated to local duties. To borrow a phrase from A E Durrant, “long years of neglect and lack of maintenance had reduced these once proud machines to wheezing hulks”! It is no surprise then that by the early 1970s all were withdrawn from service with the ubiquitous diesels now “calling the shots”. Sadly, the C1As had relatively short lives of around 27 years when other classes of steam locomotives had soldiered on for over half a century.

Over 60% of the world’s Garratts had been manufactured by Beyer-Peacock and hence became known as “Beyer-Garratts”. It is interesting to note that the first Garratt manufactured by Beyer-Peacock to H W Garratt’s concept was a tiny 33 ton 0-4-0 + 0-4-0 locomotive for a Tasmanian Railway in 1907. Quite a few units were produced on the Continent as well, most notably by Henschel of West Germany. Garratts had performed with distinction on all continents apart from North America where, as stated before, the Mallett reigned supreme. The Beyer-Garratt specifically was a fine example of British engineering at its best, sent out to serve in the far flung corners of the vast British Empire. Africa of course was synonymous with Garratts and its last bastion. It is reliably learnt that a few examples are still in active service in some form or another, on the railways of Zimbabwe and South Africa. The largest Garratts produced were the AD60 Class 4-8-4 + 4-8-4 locomotives to run on the Standard Gauge (4’ 8.5”) tracks of the New South Wales Government Railways of Australia. A static exhibit of this 260 ton behemoth is displayed in the Thirlmere Railway Museum near Sydney (See Fig 3). More recently, another AD60 has been restored to working order and has just successfully completed running trials.

Regrettably, none of the Sri Lankan Garratts have been preserved even in static form, with the withdrawn locomotives rusting away at the Dematagoda Yards. Of course for a developing country such as Sri Lanka, locomotive restoration is not a high priority item on the agenda, what with other pressing and urgent economic needs taking the fore front. However, it is noteworthy that in recent years the country has made some significant progress in this regard with the setting up of a few railway museums. It would be a wonderful initiative if the Authorities could consider preserving one of these magnificent and exceptional machines to some degree of restoration to enable its display as a static exhibit so that future generations could benefit from and enjoy the rich heritage of Sri Lanka’s railways.

After all, this is no ordinary railway locomotive. The Garratt was unique in all respects and was the undisputed king of Sri Lankan Railway’s Upcountry Main Line in the steam era.

| |

|

|

|

| Sketch 1, Schematic of Garratt Locomotive Concept |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Fig 1; C1A Garratt 345 at Nawalapitiya |

|

Fig 2; C1A Garratt 344 with a Goods Train |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Fig 3; AD60 Garratt at Thirlmere Railway Museum, near Sydney, Australia |

|

|

| |

|

| Reference : |

Garratt Locomotives of the World, A E Durrant, Bracken Books London, 1987 |

| |

Photos at Fig 1 &2, Courtesy of Basil Roberts, Fig 3 Writer’s Own |

| |

|

| Note : |

The writer also wishes to acknowledge the invaluable assistance provided by Victor Melder of Melbourne, Australia in reviewing the article. |

| |

|

|